ADME Properties¶

Info

This chapter outlines the processes that govern the time course of a drug in the body, including Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion. These processes are the determinants of onset, duration, and intensity of drug effect. Understanding the ADME processes makes it possible to design drugs with the desired pharmacokinetic profile.

Number of Pages: 90 (±2 hours read)

Last Modified: April, 2004

Prerequisites: None

Introduction¶

Therapeutics¶

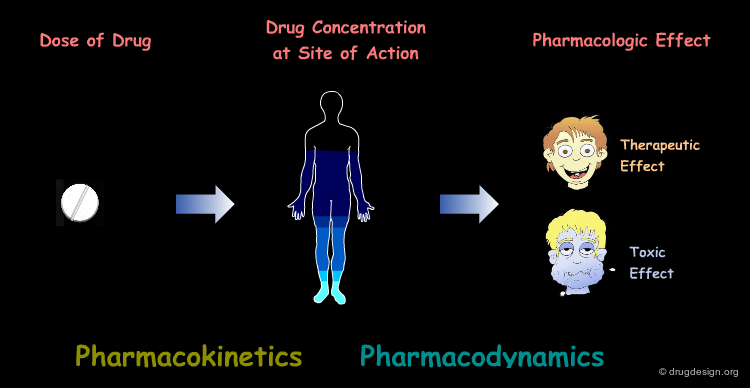

In order to produce their therapeutic effects, drugs must have a sufficient concentration in the targeted tissues. In pharmacology one assumes that there is a relationship between the therapeutic (or toxic) effect of a drug and its concentration in the site of action. Pharmacodynamics deals with the concentration-effect component whereas pharmacokinetics deals with dose-concentration.

Pharmacokinetics¶

Pharmacokinetics describes and quantifies the movement of a drug within the body, which includes the translocation and the chemical transformation of the substance. Pharmacokinetics can be defined as what the body does to the drug, including its absorption, distribution, metabolism and finally, its excretion.

Pharmacodynamics¶

Pharmacodynamics describes and quantifies the bodys' response to a drug on the physiological, biochemical and/or molecular level. Pharmacodynamics can therefore be defined as what the drug does to the body.

Dose-Response Relationships¶

Together, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics are used to design dosing regimens in which the therapeutic action is achieved with minimal adverse effects. This chapter describes the processes that govern pharmacokinetics, the time course of a drug in the body.

The Drug Route¶

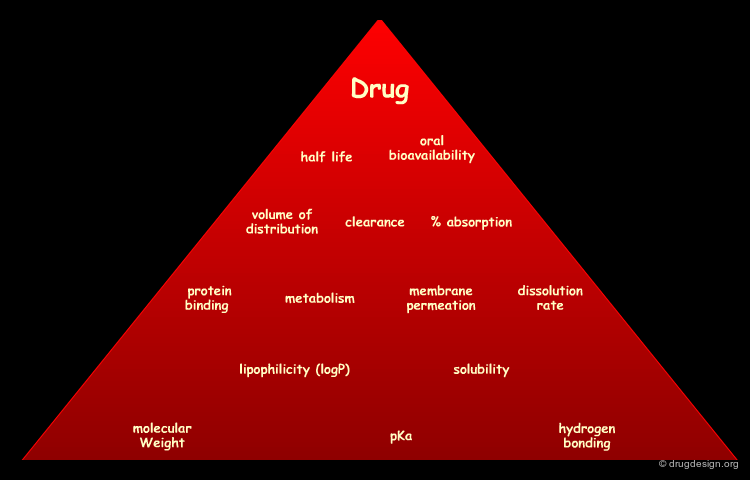

The processes involved in the time course of a drug in the body are the following: absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion, (ADME). They represent the determinants of onset, duration, and intensity of the drug effect.

Absorption¶

"Absorption" is the process during which a drug enters the body from its site of administration into the systemic circulation.

Distribution¶

"Distribution" is the process by which the drug is transferred by the blood stream throughout the body.

Metabolism¶

"Metabolism" is the biotransformation process by which the drug is enzymatically transformed into new chemical compounds (called "metabolites").

Excretion¶

"Excretion" concerns the irreversible process where the drug or its metabolites leave the body.

Bioavailability¶

Bioavailability is a pharmacokinetic term that describes the rate and extent to which the active drug ingredient enters the systemic circulation and thereby gains access to the site of action. Thus, bioavailability is concerned with how quickly and how much of a drug is present in the blood, after a specific dose is administered.

Dose-Response Relationship¶

Pharmacology hypothesizes that there is a relationship between the pharmacological effect and the concentration of a drug at the site of action. However, the drug concentration at this site of action cannot readily be measured, so instead it is measured in the blood by assuming an equilibrium between them. Bioavailability is therefore an indirect measurement of the concentration of the drug at the site of action.

Translocation of Drugs¶

"Translocation" refers to the movement of a molecule around the body. During absorption, distribution and excretion, drugs have to cross cell membranes. Membranes form the cells' physical barriers and compartments, regulating the molecular traffic across its boundaries. Normally, cells in solid tissues are so tightly compacted that many substances cannot pass through them. One important requirement for drugs is that they must be able to penetrate biological membranes.

book

Van Winkle LJ Biomembrane Transport Academic Press 1999

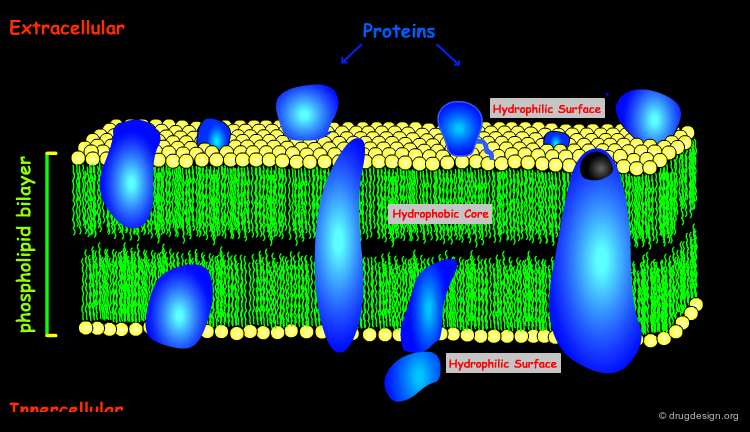

Cell Membrane Architecture¶

The architecture of the cell membrane is made of a phospholipid bilayer in which the lipidic hydrophilic polar heads rise out, and the hydrophobic tails form the core of the membrane. The tightly-packed phospholipid region contains various proteins and cholesterol molecules. Some proteins span across the entire membrane creating aqueous channels and pores.

articles

Lipids on the Frontier: a Century of Cell-Membrane Bilayers Edidin M Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4 2003

Revisiting the Fluid Mosaic Model of Membranes Jacobson K, Sheets ED and Simson R Science 268 1995

The Fluid Mosaic Model of Cell Membranes Singer S and Nicolson GL Science 172 1972

book

Gennis R Biomembranes: Molecular Structure and Function Springer-Verlag 1989

Petty H Molecular Biology of Membranes Plenum Press 1993

Sackmann E Handbook of Biological Physics. Vol. 1. Elsevier 1995

Yeagle P The Structure of Biological Membranes CRC Press 1992

Passive Diffusion¶

The most common way for a drug to cross cell membranes is by passive diffusion, a process where there is a concentration gradient. Once the concentrations on both sides become equal, a dynamic equilibrium state is achieved.

Lipid Solubility and Molecular Weight¶

The ability for a drug to cross the hydrophobic lipid bilayer is mainly governed by its lipid solubility and molecular weight. Large lipophilic molecules will diffuse more slowly than small ones.

Problems with Ionized Species¶

Ionized species have very low lipid solubility and are virtually unable to diffuse across the membranes. Small water-soluble molecules with a molecular weight of 100-200 can easily pass across a membrane through aqueous pores, however most drugs have a much higher molecular weight.

Endocytosis and Exocytosis¶

Many large molecules (such as hormones) and particles (such as viruses) can enter the cells by the process of endocytosis and exit the cell by the reverse process of exocytosis. Endocytosis develops as visualized below: uptake of the molecules into the cell (from the external environment) occurs via invagination of the plasma membrane and its internalization into membrane bound vesicles. This brings material into the cell that cannot passively diffuse (e.g. too polar) and there are no biological transporters to take it across the plasma membrane.

Carrier-Mediated Transport¶

Many cell membranes possess specialized transport machinery that regulates the molecular traffic of physiologically important molecules. These transport systems involve transmembrane proteins which bind one or more molecules, change their conformation and release the molecules on the other side of the membrane. Carrier-mediated transport proteins are chemically specific and stereospecific and process compounds that closely resemble to natural substances.

Facilitated Diffusion¶

Carrier-mediated transport proceeds with a concentration gradient similar to the passive diffusion. The process is called "facilitated diffusion" and enables qualified species to cross the membrane and reach the equilibrium rapidly.

Active Transport¶

Alternatively, carrier-mediated transport may operate to transfer molecules across the membrane against the concentration gradient. This process is called "active transport". In this case, a cellular energy is required where the translocation process is coupled either directly to ATP hydrolysis, or indirectly to the concentration gradient of another actively transported solute, such as Na+ ions.

Absorption¶

Drug Absorption¶

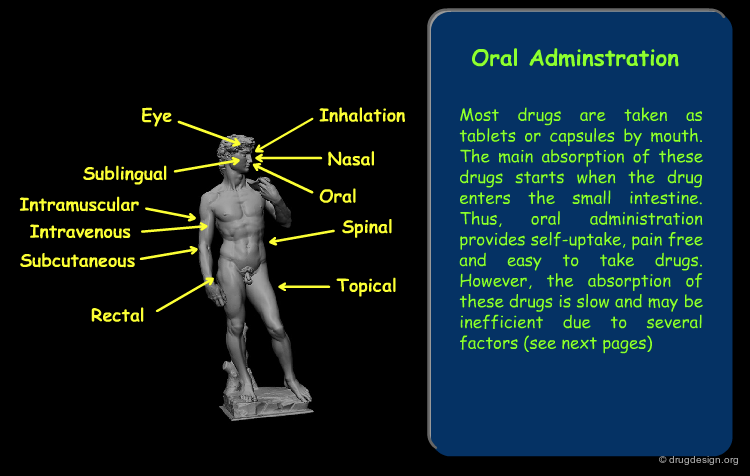

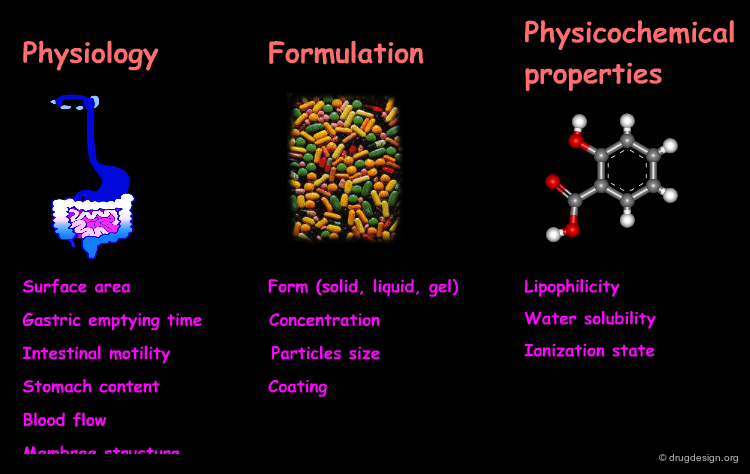

Absorption is the process of drug movement from the administration site to the systemic circulation. In this process the drug gains entrance to the body. The drug is considered outside the body until it crosses a cellular barrier such as the gastrointestinal tract or the cellular barrier of the respiratory system. Drug absorption is governed by the route of administration, the formulation and the drug's physico-chemical properties.

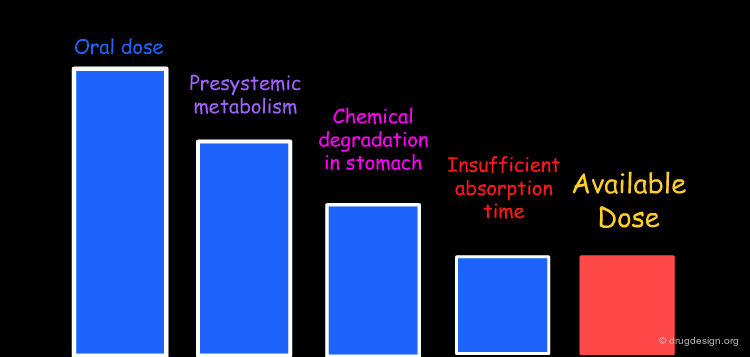

Incomplete Absorption of Drug Dose¶

The absolute bioavailability of a drug is never 100% except in IV (intra-venous) administration. Every step and every barrier crossing along the drug route is accompanied by a loss in drug dose. During the absorption phase the main causes for drug loss of orally administrated drugs are: (1) drug metabolism (such as bacterial, gut wall, and first pass metabolism by the liver) before reaching the systemic circulation; (2) chemical degradation by the acidic environment in the stomach and (3) partial absorption due to limited residence time in the gastrointestinal tract.

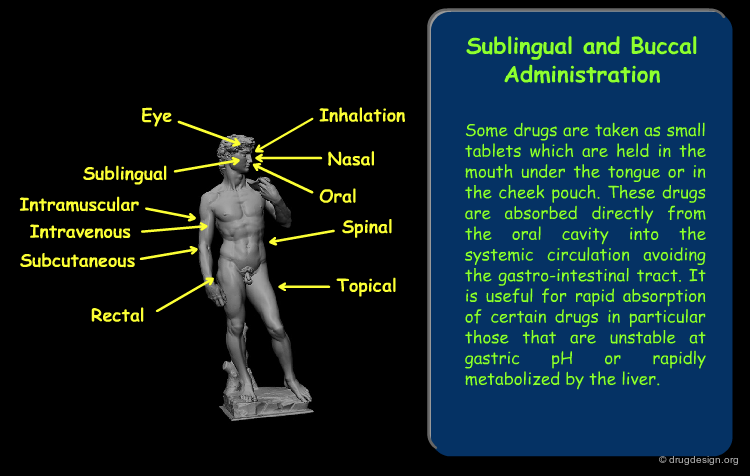

Routes of Administration¶

The drug route in the body starts with its absorption from the site of administration. The absorption varies greatly according to the route of exposure. The main routes of administration are presented here. Click on each term for more detail.

book

Oie S and Benet LZ Modern Pharmaceutics, 4th edition Marcel Dekker 2002

Properties of Drugs that Influence Absorption¶

The rate and extent of absorption of orally administered drugs is influenced by many factors. These include physiological parameters, formulation, and the intrinsic physico-chemical properties of the drug's active ingredient. The physico-chemical properties that influence the bioavailability of the drug are discussed on the following pages.

articles

Physicochemical Profiling (Solubility, Permeability and Charge State) Avdeef A Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 1 2001

book

Oral Drug Absorption: Prediction and Assessment (Drugs and the Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vol. 106) Marcel Dekker 2000

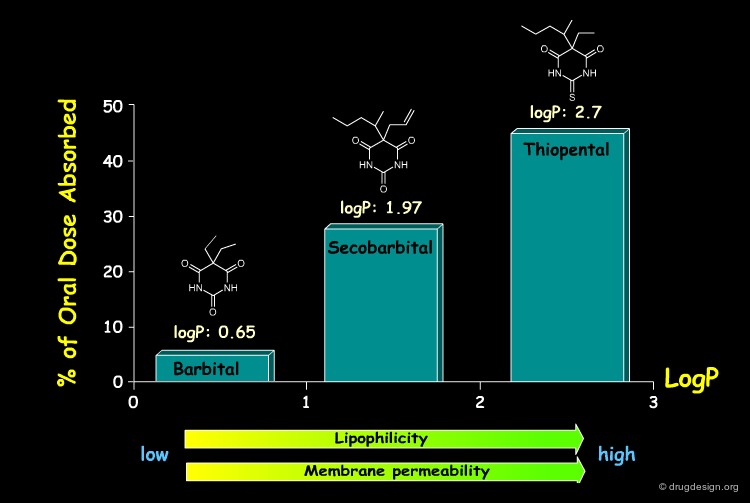

Lipophilicity and Membrane Penetration¶

Lipophilic non-polar substances dissolve easily in lipid membrane layers and can penetrate into cells by passive diffusion. As a general rule, by increasing the lipophilicity of a molecule (by increasing its content in non-polar moieties) will facilitate its penetration through membrane barriers and increase its concentration in the blood stream. In some cases (as in the barbital series shown below) the extent of absorption can be directly correlated with the lipophilicity of the molecule.

articles

Mass Transport Phenomena and Models: Theoretical Concepts Flynn GL, Yalkowsky SH, and Roseman TJ J. Pharm. Sci. 63 1974

Partition Coefficient and their Uses Leo A, Hansch C, and Elkins D Chem. Rev. 71 1971

book

Dawson DC Handbook of Physiology, Sect. 6: The Gastrointestinal System, Vol. IV, Intestinal Absorption and Secretion Amer. Physiol. Soc 1991

Sangster J Octanol-Water Partition Coefficients: Fundamentals and Physical Chemistry John Wiley and Sons 1997

Weiss TF Cellular Biophysics. Volume I: Transport The MIT Press 1996

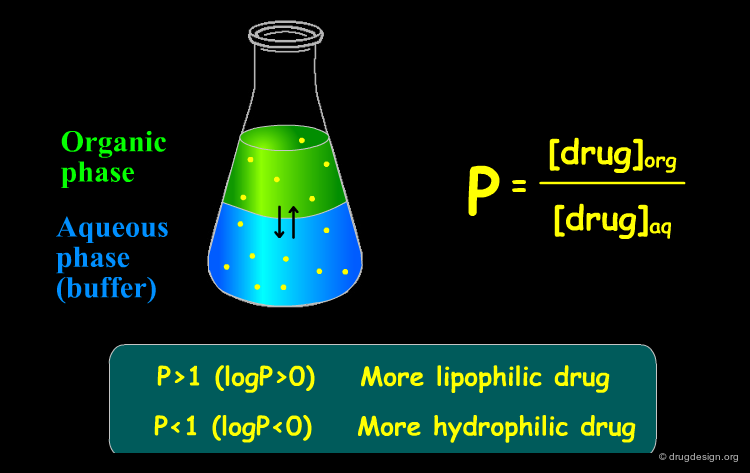

The Partition Coefficient¶

A good indicator of the in-vivo ability of a molecule to penetrate a membrane is the "partition coefficient", a descriptor which characterizes the compound lipophilicity. The partition coefficient (defined as P or logP) derives from the measure of the partitioning of the compound between a lipidic phase and an aqueous phase, taken as a biological membrane model. Although membrane proteins are more complex, this model provides an easy access to a quantitative measure of the lipophilicity of a molecule.

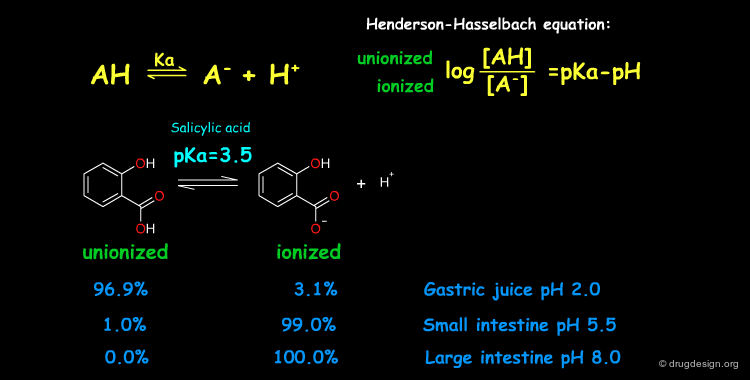

pKa of a Drug and pH¶

Many drugs are weak acids or bases and therefore exist in both un-ionized and ionized form. The ratio between the two forms is governed by the pKa (ionization equilibrium constant) of the drug and the pH of the body site. Since only the un-ionized species can diffuse through membranes, the pH and the pKa dictate the amount of un-ionized drug available for passive diffusion. A weak acid and a weak base are presented here to illustrate the situation at different pH (sites).

articles

The Gastric Secretion of Drugs: A pH Partition Hypothesis Shore PA, Brodie BB, and Hogben CAM J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 119 1957

book

Albert A and Serjeant EP The Determination of Ionization Constants, 3rd ed. Chapman and Hall 1984

Perrin DD, Dempsey B, and Serjeant EP pKa Prediction for Organic Acids and Bases Chapman and Hall 1981

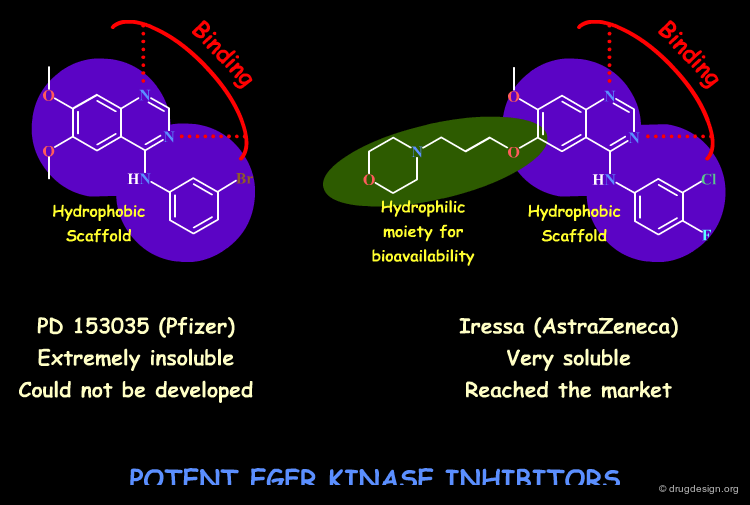

Water Solubility and Dissolution¶

The solubility requirement of a drug is dual: on one hand the drug has to possess lipophilic properties to penetrate cell membranes, and on the other hand it has to be hydrophilic enough to avoid precipitation in the aqueous media (e.g. gastrointestinal tract, blood). Water solubility is of crucial importance for the absorption (many drugs are given in a solid dosage form and must dissolve before absorption can take place). Dissolution is the rate-limiting step in the absorption of many low solubility drugs. The incorporation of an ionizable center in the molecule such as an amine will increase its water solubility.

articles

Influence of Physicochemical Properties on Dissolution of Drugs in the Gastrointestinal Tract Horter D and Dressman JB Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46 2001

book

DJW Grant and Higuchi T Solubility Behavior of Organic Compounds John Wiley and Sons 1990

Yalkowsky SH, and Banerjee S Aqueous Solubility: Methods of Estimation for Organic Compounds Marcel Dekker 1992

Distribution¶

Drug Distribution¶

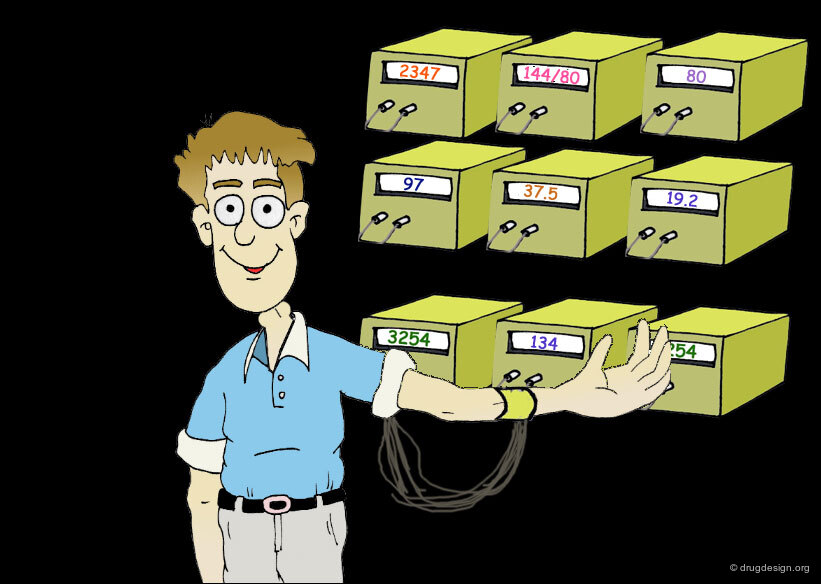

After entering the systemic circulation, the drug is distributed to the body tissues. This is a reversible process where an equilibrium is reached. In human pharmacology it is not possible to measure the rate and the extent of drug distribution in specific tissues. However indirectly, it is possible to get useful information by measuring the drug concentration in the plasma, as explained on the following pages.

Drug Translocation and Distribution¶

When the drug enters into the blood plasma, it acquires very fast long-distance bulk flow transfer. Since, virtually all tissues have blood supply, they are all potentially exposed to the absorbed drug. Distribution of the drug from the blood vessels to body cells and tissues usually require passive diffusion transfers.

Site of Action¶

The greatest efforts in drug design are spent on the distribution of a drug to its site of action (where its pharmacological effect is obtained). For most drugs the site of action is at a specific macromolecule, such as proteins (which may function as receptors, ion channels, enzymes, carrier molecules etc.), and nucleic acids. Here, for example, is shown the anticancer drug methotrexate bound to its target enzyme, dihydrofolate reductase (ribbon representation).

Distribution is to Many Body Sites¶

Only a small portion of the dose actually reaches the site of action. The drug is usually distributed to many body tissues, other than those involved in its pharmacological effect. Distribution to these tissues is important in determining the pharmacokinetic behavior of the drug.

Apparent Volume of Distribution¶

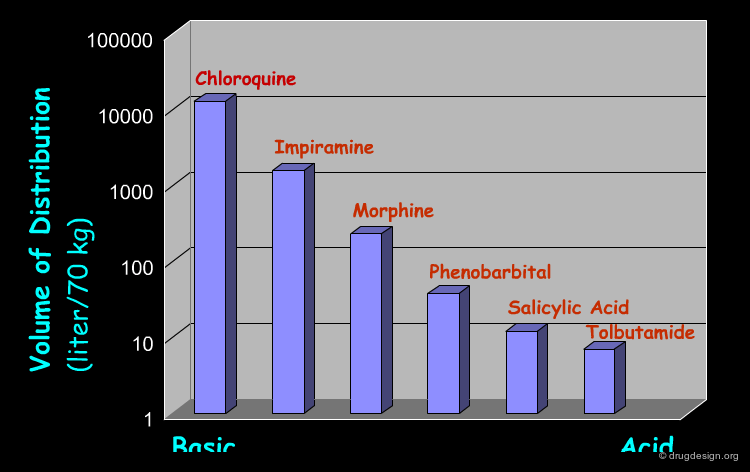

The total volume of fluid into which a drug appears to be distributed is called "apparent volume of distribution" (Vd). This is the ratio between the amount of drug in the body (at equilibrium), and the concentration of the drug measured in the plasma. The amount of drug in the body can be correlated with the drug dose; thus, Vd provides a reference for the drug plasma concentration expected for a given dose, and for the dose required to produce a given concentration.

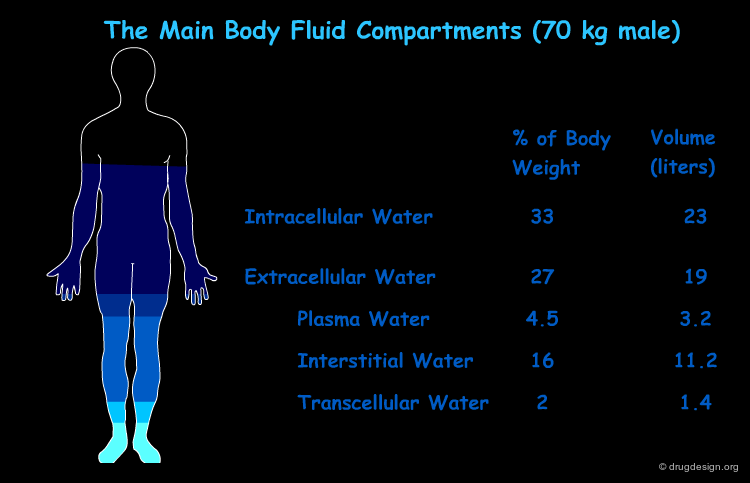

Vd and Drug Distribution Patterns¶

Sometimes Vd might approach the plasma volume (3.2 liter/70 kg), a low value compatible with a drug that remains largely within the vascular system (such as the plasma substitute, dextran). For other drugs it might approach the volume of total body water (42 liter/70 kg) that is compatible with drugs that are uniformly distributed throughout the body water. This is the case of low molecular weight water soluble compounds such as ethanol.

Meaning of Vd¶

Vd should not be mistakenly considered as a physical description of the real physiological volumes. Furthermore, Vd cannot provide too much information about the specific pattern of distribution (even if it happens to approach the previously indicated values). Since only an unbound drug is distributed, and since most drugs have specific tissue binding and different extents of plasma protein binding, these drugs can exibit a wide range of Vd values. For example, many acidic drugs tend to bind to plasma proteins and have small Vd values, whereas many basic drugs tend to be bound by tissues and have large Vd values.

Factors that Influence Drug Distribution¶

The rate of distribution to the different tissues depends on the blood perfusion and the membrane permeability, whereas the extent of distribution to the different tissues depends on the drug lipophilicity, ionization state, plasma proteins binding, and tissue binding.

Perfusion and Membrane Permeability¶

The rate of distribution is related to either the perfusion (i.e. blood flow per tissue mass) or to the rate-limited diffusion. Sometimes a perfusion rate-limitation can occur when a tissue membrane presents no barrier to distribution, as demonstrated for small lipophilic drugs moving into some tissues. In this case, the distribution equilibrium (entry and exit rate are the same) is reached more rapidly in highly perfused regions than in poorly perfused tissues (see diagram below). Diffusion rate-limited distribution can occur for drugs with low membrane penetration ability, or in specific tissues with low membrane permeability (two cases explained in this chapter).

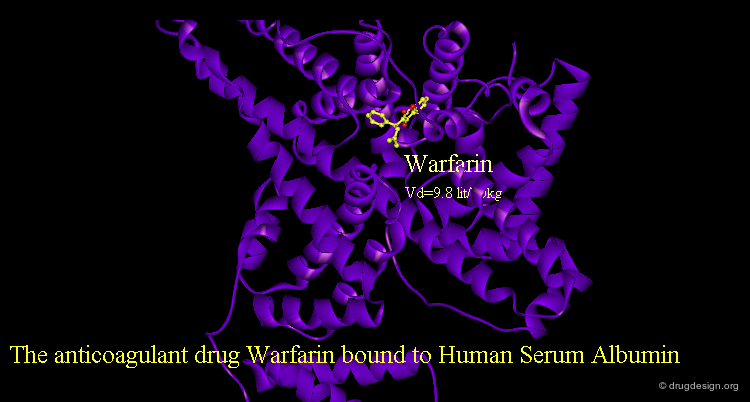

Binding to Plasma Proteins¶

Drugs that are transported in the blood stream may associate with plasma proteins to different extents. The fraction of drug that is free in the plasma aqueous solution may be low (e.g. 1%). In this context the most important proteins are Albumin, α1-acid glycoprotein and lipoproteins. Acidic drugs are generally bound more extensively to albumin, and basic drugs to α1-acid glycoprotein and lipoproteins. The free (non-bound) fraction of a drug is in equilibrium with the bound fraction; however only the free drug can further diffuse.

articles

Crystal Structure Analysis of Warfarin Binding to Human Serum Albumin: Anatomy of Drug Site Petitpas I, Bhattacharya AA, Twine S, East M, and Curry S J Biol. Chem 276 2001

Accumulation in Organs and Tissues¶

Usually drugs are not uniformly distributed to all body tissues. The concentration of some drugs can be either significantly higher or lower in specific tissues. For example Chloroquine is found in high concentrations in the eye due to its high affinity to the retinal pigment melanin. Tetracyclines accumulate slowly in bones and teeth because of their affinity to calcium, whereas the highly lipophilic drug Thiopental accumulates in the adipose tissue (see diagram below). Accumulation is usually a reversible equilibrium process and as such the accumulating organ can function as a drug reservoir.

articles

Thiopental Pharmacokinetics. Bischoff KB, Dedrick RL. J. Pharm. Sci. 57 1968

Ion Trapping¶

In general only the un-ionized portion of the drug can cross the membrane barriers and this can lead to the accumulation of the ionized form in a body compartment ("ion trapping"). For example, if the plasma is more basic than the tissue, basic drug ionization is reduced and more of the un-ionized form of the drug can easily move from the plasma to the tissue where it then becomes more ionized and cannot get back. The reverse trapping mechanism can occur for acids (click the pKa scale).

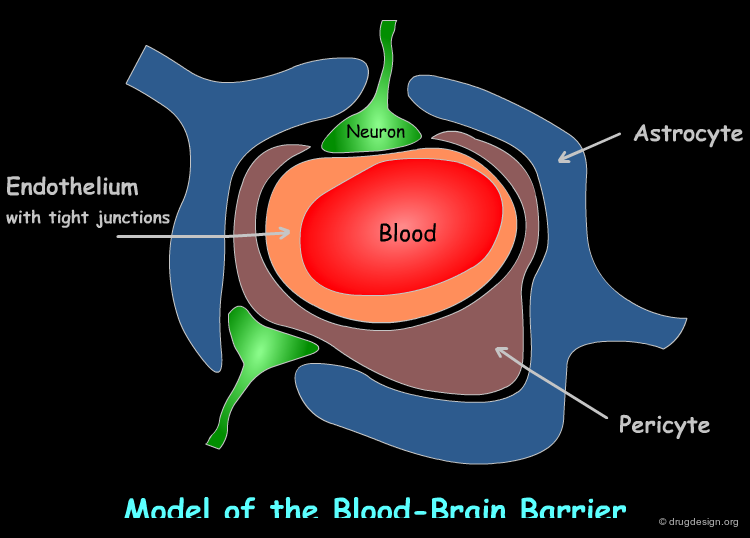

Biological Barriers (BBB, Placental, Blood-Testis)¶

Our body includes some special membrane barriers such as the barrier between the blood and the brain (the blood-brain barrier), the barrier between the foetus and the mother (placental-barrier), and the barrier between the blood and the testes (blood-testis). These barriers are not permeable and often dictate diffusion rate-limited drug transfer. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) consists of a layer of tightly apposed endothelial cells (see diagram) that permit transport by passive diffusion of only small (up to molecular weight of 500 Da) and highly lipophilic drugs.

articles

The Blood-Brain Barrier: Principles for Targeting Peptides and Drugs to the Central Nervous System Begley DJ J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 48 1996

Drug Delivery to the Central Nervous System: a Review Misra A, Ganesh S, Shahiwala A and Shah SP J Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 6 2003

Drug and Gene Targeting to the Brain with Molecular Trojan Horses Pardridge WM Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1 2002

Neuroprotection in Transient Focal Brain Ischemia after Delayed Intravenous Administration of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor Conjugated to a Blood-brain Barrier Drug Targeting System Zhang Y, Pardridge WM Stroke 32 2001

Conjugation of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor to a Blood-brain Barrier Drug Targeting System Enables Neuroprotection in Regional Brain Ischemia Following Intravenous Injection of the Neurotrophin Zhang Y, Pardridge WM Brain Res. 889 2001

Pdb

BDNF structure: PDB entry: 1B8M

The structure of complex between neurotrophic factor, Neurotrophin-4 and TRKB, PDB entry: 1HCF

book

Pardridge WM Brain Drug Delivery: The Future of Brain Drug Development Cambridge Univ. Press 2001

BBB can be Crossed with Active Transport Systems¶

In addition, the BBB can be crossed with few active transport systems such as (1) a carrier-mediated transport that catalyzes a bidirectional movement of small polar nutrients (e.g. glucose, amino acids, nucleosides); (2) receptor-mediated transcytosis that comprise peptide-specific receptors (e.g. insulin receptor, transferrin receptor) that enable endocytosis or exocytosis of specific peptides and proteins; (3) active-efflux transport systems that mediate the removal of metabolic by-products and other molecules from the brain to the blood. As a consequence, even drugs that slowly penetrate the BBB may never achieve sufficient therapeutic brain concentration.

Chimeric Peptide Technology in Brain Drug Delivery¶

One promising possibility in brain drug delivery, exploits the active transport systems by employing chimeric peptide technology. In this method, a non-transportable drug is conjugated to a BBB transport vector (a specific peptide that undergoes receptor-mediated endocytosis). For example, the binding of the neurotrophic factor BDNF to a specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) generates a bifunctional molecule that on one side binds the neurotrophic tyrosine-kinase receptor (TRKB) on neurons to mediate neuroprotection, and on the other side binds to one of the receptor at the BBB to mediate transport from the blood to the brain.

Distribution as Equilibrium State¶

The distribution of a drug consists of many equilibrium processes and all of them together determine the rate and extent of the drug distribution. The drug concentration in the site of action cannot be reflected by the plasma concentration until the tissue distribution equilibrium has been reached (tissue entry and exit rates are equal). However, the distribution process may be more complex since it occurs simultaneously alongside metabolism and excretion.

Metabolism¶

Metabolism of Foreign Substances (Xenobiotics)¶

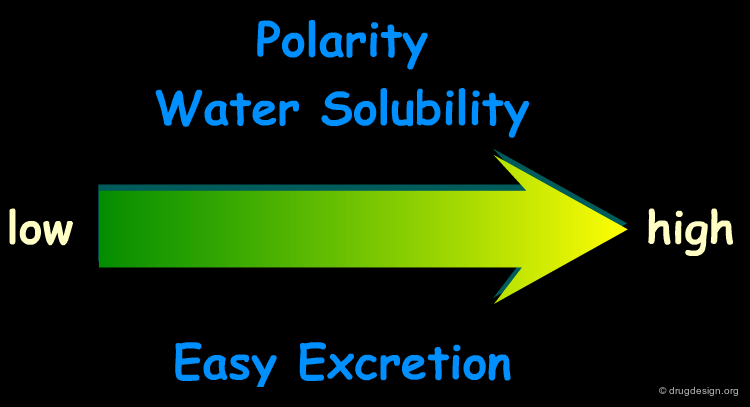

Our body has evolved complex systems to protect itself from foreign substances which are called "xenobiotics". The primary route is the elimination by enzymatic modification of the xenobiotic molecule into a generally more water-soluble molecule that can be more easily eliminated from the body. This chemical modification process is called "metabolism" or "biotransformation".

Metabolic Reactions¶

Drug molecules are designed to be lipophilic so that they can penetrate membrane barriers by passive diffusion. Drug metabolism is essentially the opposite process that introduces hydrophilic moieties onto the drug molecule to make it more water soluble. The compound does not reach the site of action, but in addition it is transformed to ease its elimination by excretion.

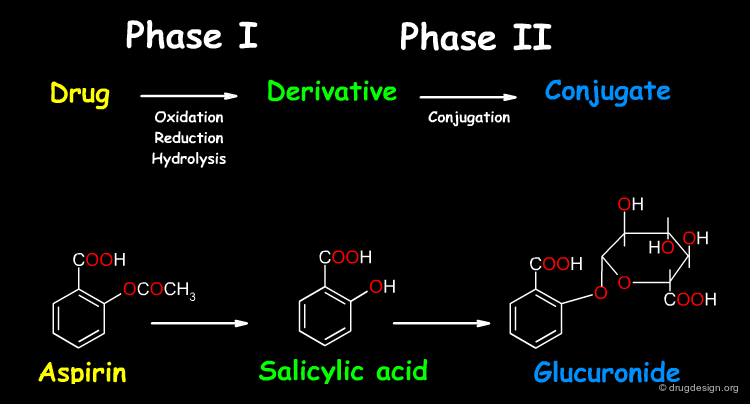

Pathways of Metabolism¶

For many drugs, metabolism occurs in two apparent phases: (1) phase I is the introduction of a new functional group on the molecule and (2) phase II is the creation of a new conjugated molecule by connecting a small endogenous molecule to the functional group created. Note that these phases do not necessarily occur sequentially and that a drug can take both or either one of these two pathways.

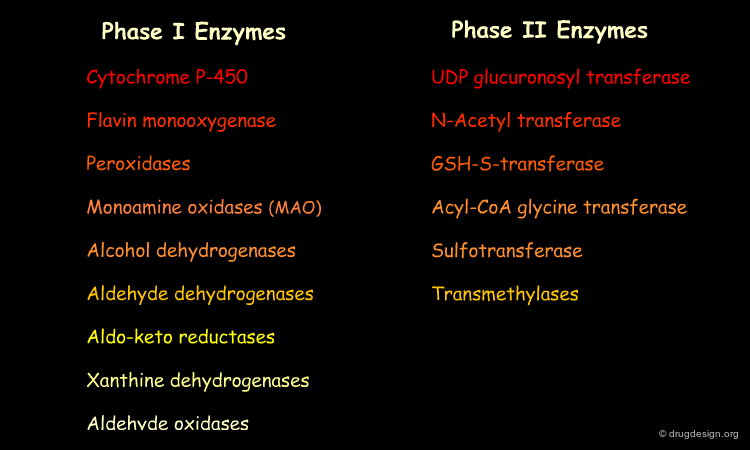

Chemistry of Phase I Metabolism¶

In phase I reactions, a new small polar group is either exposed on the drug, or added to the drug. There is a wide range of phase I reactions including oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis (see examples below). The drug as well as the drug products ("metabolites") can be subjected to successive phase I reactions, leading to many metabolites.

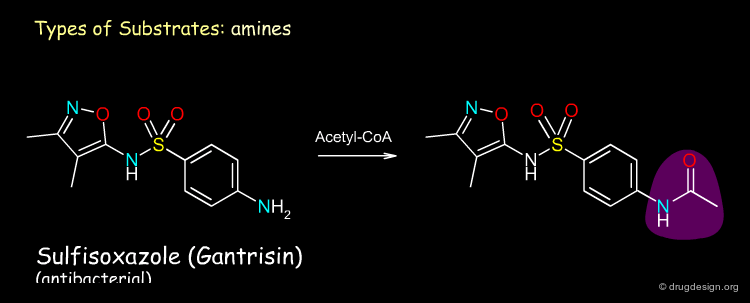

Chemistry of Phase II Metabolism¶

Phase II reactions include conjugation reactions in which an endogenous molecule (e.g. glucuronic acid or sulfate - see examples below), is added to a phase I metabolite or to the drug itself. The prerequisite for the conjugation reaction is for the molecule to have a suitable reactive functional group (e.g. OH, NH2, COOH) to which the endogenous substrate can be attached.

Metabolic Activation and Toxification¶

Drug metabolism is a complicated process. Often, a drug is metabolized into major and minor products. The different metabolites can be either pharmacologically active or inactive (inert) or even toxic. Furthermore, in some cases the substance becomes pharmacologically active only after it has been metabolized. Such substances, for which only the metabolite is active, are called "pro-drugs". Some examples of pathways are illustrated here.

Sites of Drug Metabolism¶

The enzymes involved in drug metabolism are present in many tissues (e.g. kidney, lung, and gastrointestinal tract); however, these enzymes are by far more concentrated in the liver, making it the major site of drug metabolism. When a drug is administrated orally, it undergoes metabolism in the gastrointestinal tract and in the liver before reaching the systemic circulation. This process is called "first-pass metabolism". For some drugs, the first pass effects limit so seriously the bioavailability of the compound, that alternative routes of administration must be employed to achieve therapeutically effective blood levels.

Drug Metabolizing Enzymes¶

Although there are biotransformations of the drug that can occur spontaneously in vivo, most drug metabolism in the body is catalyzed by specific cellular enzymes. Inside the cell many enzymes are located in the endoplasmic reticulum (referred to as "microsomal enzymes" due to their isolation method). Other enzymes are located in the mitochondria, cytosol, lysosomes, or in the cell membrane. Major drug metabolizing enzymes are listed below.

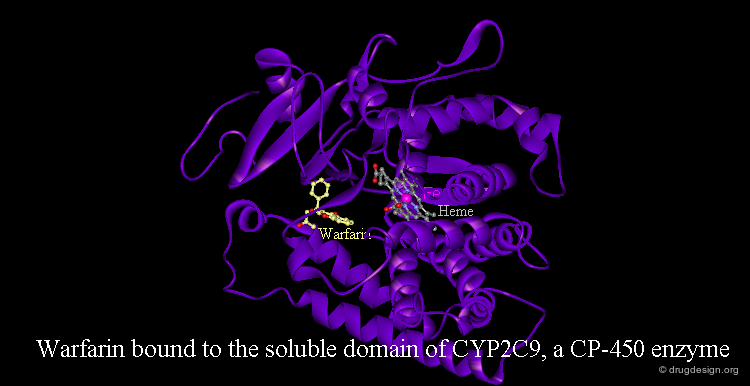

Cytochrome P-450 (CYP)¶

The most important phase I metabolism enzymatic system is the cytochrome P-450 (CYP), a heme protein superfamily. There are more than 50 CYP families (homology >40%) with up to 10 subfamilies (homology >55%). CYP enzymes are localized in the liver, but also in the small intestine, kidneys, lungs, and brain. They are embedded in the phospholipid bilayer of the endoplasmatic reticulum with a portion exposed to the cytosol. The crystallographic structure of several CYP enzymes has been elucidated. The example visualized below represents the anticoagulant drug Warfarin bound to the human cytochrome P-450 CYP2C9 enzyme.

articles

P450 Structures and Oxidative Metabolism of Xenobiotics Lewis DFV Pharmacogenomics 4 2003

Human cytochromes P450 associated with the phase 1 metabolism of drugs and other xenobiotics: a compilation of substrates and inhibitors of the CYP1, CYP2 and CYP3 families Lewis DFV Curr. Med. Chem. 10 2003

book

Lewis DFV Guide to Cytochromes P450: Structure and Function Taylor and Francis 2001

Oxidative Metabolism by Cytochrome P-450 Enzymes¶

CYP enzymes catalyze the oxidation of many drugs, environmental xenobiotics, food toxins and endogenous substances (e.g. steroid hormones, fatty acids, and prostaglandins). Different CYP450 enzymes have distinct, but often overlapping, substrate specificities. The following five CYP450 enzymes are the major drug-metabolizing enzymes that contribute to the oxidative metabolism of most drugs in current clinical use. Move the cursor over each enzyme listed to see examples of its substrate drugs.

articles

P450 Structures and Oxidative Metabolism of Xenobiotics Lewis DFV Pharmacogenomics 4 2003

Human cytochromes P450 associated with the phase 1 metabolism of drugs and other xenobiotics: a compilation of substrates and inhibitors of the CYP1, CYP2 and CYP3 families Lewis DF Curr. Med. Chem. 10 2003

Interindividual Variations in Human Liver Cytochrome P-450 Enzymes Involved in the Oxidation of Drugs, Carcinogens and Toxic chemicals: Studies with Liver Microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, Inui Y, and Guengerich FP J. Pharmacol. Exp. There. 270 1994

book

Lewis DFV Guide to Cytochromes P450: Structure and Function Taylor and Francis 2001

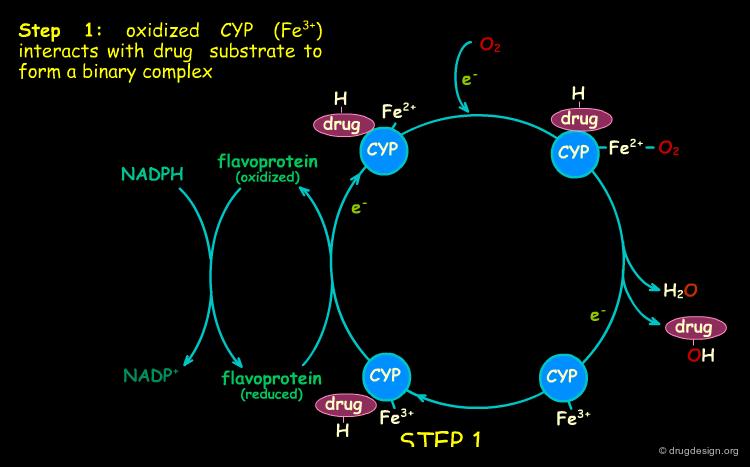

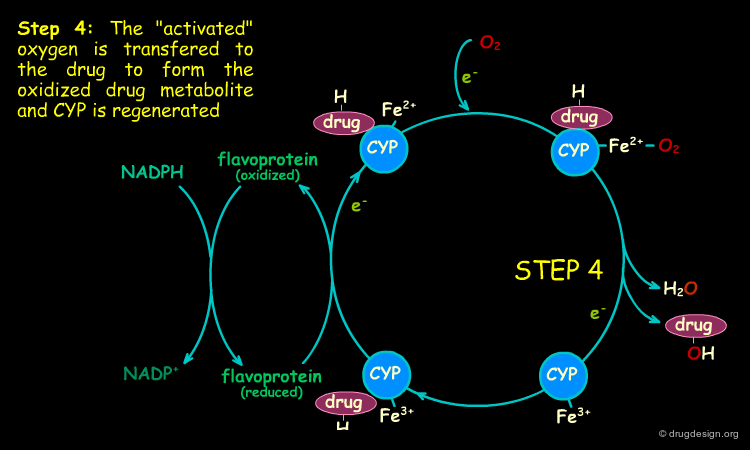

Mechanism of Cytochrome P-450 Oxidation¶

CYP are oxygenase enzymes in which one oxygen atom of O2 is introduced into the substrate in an electron transfer process. The electrons are supplied by the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (a flavoprotein that transfers electrons from NADPH (nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate) to cytochrome P450). The scheme of a typical oxidative cycle is presented below. The potent oxidizing properties of the intermediates created in this cycle enable the oxidation of many structurally unrelated substrates.

articles

P450 Structures and Oxidative Metabolism of Xenobiotics Lewis DFV Pharmacogenomics 4 2003

Human cytochromes P450 associated with the phase 1 metabolism of drugs and other xenobiotics: a compilation of substrates and inhibitors of the CYP1, CYP2 and CYP3 families Lewis DF Curr. Med. Chem. 10 2003

book

Lewis DFV Guide to Cytochromes P450: Structure and Function Taylor and Francis 2001

Metabolic Variability¶

Differences in metabolism can dramatically influence the effectiveness or toxicity of drugs which are directly related to the plasma concentration of the drug. Metabolism is a function of genetically determined factors including species, age, gender and inherited variability (polymorphisms) as well as external factors like nutrition, disease state, dose, and exposure to other chemicals that can inhibit or induce enzymatic activity. In the following pages some examples are presented.

Genetic Polymorphisms¶

Genetic polymorphism refers to inherited differences in drug metabolism. For example, the phase II acetylation reaction by N-acetyl transferase is influenced by genetic differences. A "slow-acetylator" phenotype occurs in about 50% of Blacks and Whites in the USA, and is much less common in the Asian population. The antituberculosis drug Isoniazid is an example of a high risk drug for this case of phenotype where toxic effects such as nerve and liver damage can occur. The absence of the enzyme in this phenotype results in high plasma concentrations for the drug, exceeding its toxic threshold (see diagram).

articles

Genetic Control of Isoniazid Metabolism in Man Evans DAP, Manley KA and McKusick VA Br. Med. J. 2 1960

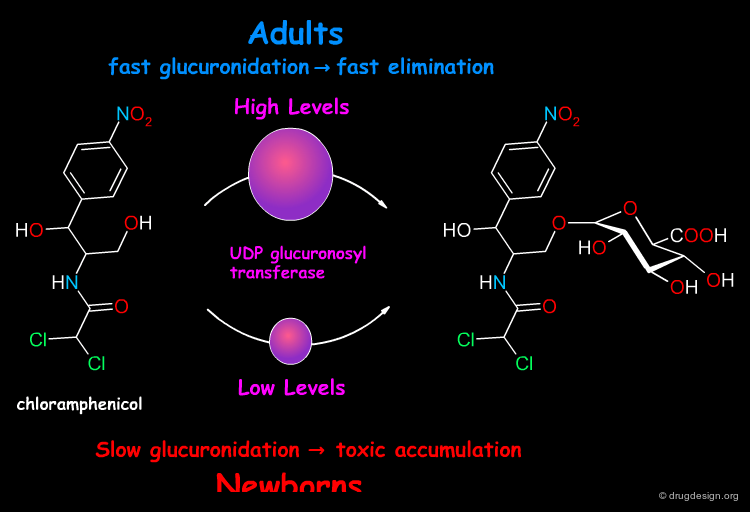

Age¶

Biotransformation capabilities are reduced in newborns and also in the old age. A fatal example of a toxic effect in newborns occured in the late 1950s with the antibiotic chloramphenicol. Normally metabolized in the liver to the inactive glucuronide, the drug was found to be converted in newborns at a slower rate, resulting in toxic concentrations of chloramphenicol in the plasma.

articles

The Development of Drug Metabolizing Enzymes and Their Influence on the Susceptibility to Adverse Drug Reactions in Children Johnson TN Toxicology 192 2003

Clinical Pharmacokinetics in Newborns and Infants. Age-Related Differences and Therapeutic Implications Morselli PL, Franco-Morselli R., and Bossi L Clin. Pharmacokinet. 5 1980

Chloramphenicol in the Newborn Infant Weiss CF, Glasko AJ, and Weston JK New Engl. J. Med. 262 1960

A Drug Metabolism Inhibited by Another Drug¶

In some cases, exposure to one xenobiotic substance can interfere with the metabolism of another. Of particular clinical importance is the situation in which the metabolism of one drug is inhibited by another drug. For example, the pro-drug terfenadine is metabolized by CYP3A4 and converted into the pharmacologically active antihistaminic metabolite fexofenadine. The antifungal drug ketoconazole blocks the CYP3A4 terfenadine metabolism, which then accumulates in toxic amounts and can result in fatal cardiac arrhythmias.

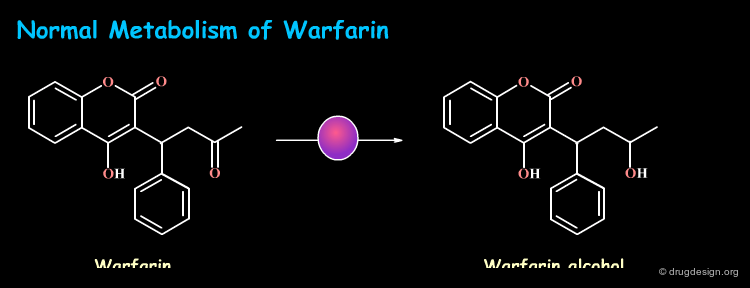

Metabolism Increased by Enzymatic Induction¶

In some cases, prior exposure to one xenobiotic can enhance the metabolic capacity for another xenobiotic. Examples of enzyme inducers are ethanol, tobacco and drugs like barbiturates. Exposure to these substances increases the production of particular enzymes and results in the increase of their overall metabolic activity. For example, patients who routinely ingest barbiturates may require considerably higher doses of the anticoagulant Warfarin to overcome its faster metabolism and maintain its therapeutic action.

Metabolism and Drug Design¶

Metabolism is one of the most important determinants of the pharmacokinetic profile of a drug. Low metabolic stability (highly metabolized compound) usually leads to a poor bioavailability and fast elimination. Furthermore, the metabolic transformation of a drug can lead to active and toxic metabolites that influence directly the pharmacological outcome. A good understanding of drug metabolism can optimize the metabolic stability of a compound and lead to the design of better drugs. In the following pages some examples of approaches that control and take advantage of metabolism in drug design are presented.

articles

The Use of In Vitro Metabolism Studies in the Understanding of New Drugs Chiu S-HL J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 29 1993

Role of Metabolism and Pharmacokinetic Studies in the Discovery of New Drugs - Present and Future Perspectives Humphrey MJ and Smith DA Xenobiotica 22 1992

Role of Drug metabolism in Drug Discovery and Development Kumar GN and Surapaneni S Med. Res. Rev. 21 2001

Role of Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism in Drug Discovery and Development Lin JH, Lu AYH Pharmacol. Rev. 49 1997

Design of Drugs through a Consideration of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics Smith DA Eur. J. Drug. Metab. Pharmacokinet. 19 1994

Design of Drugs Involving the Concepts and Theories of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics Smith DA, Jones BC, and Walker DK Med. Res. Rev 16 1996

Early ADME in Support of Drug Discovery:the Role of Metabolic Stability Studies Thompson TN Curr. Drug Meta 1 2000

Optimization of Metabolic Stability as a Goal of Modern Drug Design Thompson TN Med. Res. Rev. 21 2001

Property-Based Design: Optimization of Drug Absorption and Pharmacokinetics van de Waterbeemd H, Smith DA, Beaumont K,and Walker DK J. Med. Chem. 44 2001

High-Throughput Screening in Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetic Support of Drug Discovery White RE Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 40 2000

Hard Drugs¶

In general, metabolism can be reduced by the incorporation of stable functions (blocking groups) at metabolically vulnerable sites. This approach has been described as the production of "hard" drugs where the goal is to prevent metabolism. Enhancing metabolic stability has proved in many cases to increase bioavailability and decrease the drug elimination rate. Many strategies have been used in this type of approach, some examples are illustrated here.

articles

Optimization of Metabolic Stability as a Goal of Modern Drug Design Thompson TN Med. Res. Rev. 21 2001

Metabolism and Structure Activity Data Based Drug Design: Discovery of (-) SCH 53079 an Analog of the Potent Cholesterol Absorption Inhibitor (-) SCH 48461 Dugar S, Yumibe N, Clader JW, Vizziano M, Huie K, Van Heek M, Compton DS, and Davis Jr HR Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.

1996

Benzazepinone Calcium Channel Blockers. 2. Structure-Activity and Drug Metabolism Studies Leading to Potent Antihypertensive Agents. Comparison with Benzothiazepinones Floyd DM, Kimball SD, Krapcho J, Das J, Turk CF, Moquin RV, Lago MW, Duff KJ, Lee VG, White RE, et al. J. Med. Chem. 35 1992

Synthesis of a Series of Compounds Related to Betaxolol, a New beta 1-Adrenoceptor Antagonist with a Pharmacological and Pharmacokinetic Profile Optimized for the Treatment of Chronic Cardiovascular Diseases Manoury PM, Binet JL, Rousseau J, Lefevre-Borg F, and Cavero IG J. Med. Chem 30 1987

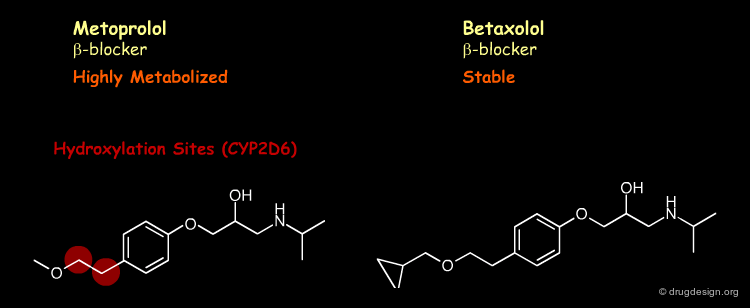

Removing¶

The strategy is to (1) remove the vulnerable site by replacing the carbon by an oxygen atom and (2) further block with a halogen atom the formed phenoxy moiety at the para position (moiety known to be susceptible to aromatic hydroxylation at this location).

Hiding¶

The strategy is the introduction of a cyclopropyl group, which creates steric hindrance and prevents betaxolol from binding efficiently to the active site of the metabolizing enzyme.

Stabilizing¶

The strategy is the stabilization of the nitrogen atom in terms of electron abstraction, which is needed in the demethylation metabolic process.

Soft Drugs¶

"Soft drug design" aims at designing a substance with a predictable metabolism producing inactive metabolites, after the biological action is elicited. Soft drugs are obtained by building into a lead compound (with the desired activity) a metabolically sensitive group which will direct the molecule to a metabolic pathway of deactivation and detoxification. The preferred targets for soft drugs are the hydrolytic enzymes such as esterases which are present in most tissues and offer a fast reaction and a low substrate specificity. The examples presented here illustrate some of the concepts taken into account in soft drug design.

articles

Retrometabolic Drug Design - Novel Aspects, Future Directions Bodor N Pharmazie 56 Suppl 1 2001

Soft Drug Design: General Principles and Recent Applications Bodor N and Buchwald P Med. Res. Rev. 20 2000

Soft Drugs. 1. Labile Quaternary Ammonium Salts as Soft Antimicrobials Bodor N, Kaminski JJ, and Selk S J. Med. Chem. 23 1980

Ultra-Short-Acting beta-Adrenergic Receptor Blocking Agents. 2. (Arlyoxy)propanolamines Containing Esters on the Aryl Function Erhardt PW, Woo CM, Anderson WG, and Gorczynski RJ. J. Med. Chem. 25 1982

Structure-Activity Relationships and Electrophysiological Effects of Short-Acting Amiodarone Homologs in Guinea Pig Isolated Heart Morey TE, Seubert CN, Raatikainen MJP, Martynyuk AE, Druzgala P. Milner P, Gonzalez MD, and Dennis DM. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 297 2001

Electrophysiological Effects of a Novel, Shortacting and Potent Ester Derivative of Amiodarone, ATI-2001, in Guinea Pig Isolated Heart Raatikainen MJP, Napolitano CA, Druzgala P, and Dennis DM J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 277 1996

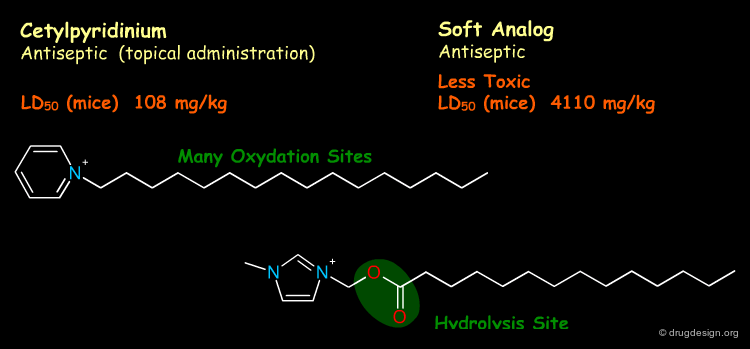

Topical Use¶

Introducing an ester moiety creates a close analog of the active drug that enables fast, one-step deactivation by esterases. In topical applications, soft drugs should act locally, and be rapidly deactivated and eliminated upon entering the blood stream.

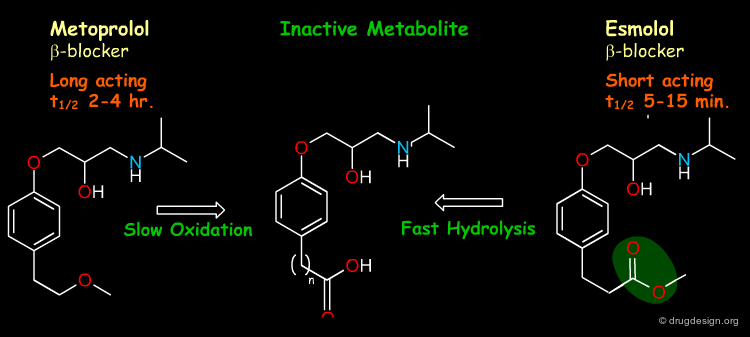

Ultrashort Use¶

Introducing the ester moiety in esmolol creates a close analog of metoprolol with a "shared" inactive metabolite. Thus, by overpassing the relatively slow oxidation steps, esmolol has a ultrashort effect and hence better control of plasma drug levels in IV adminstration. The soft drug design here starts with the known inactive metabolite.

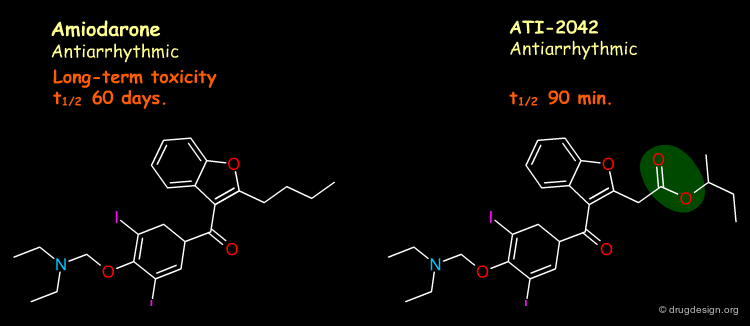

Oral Use¶

Introducing an ester moiety creates a close analog of the active drug that enables faster, one-step deactivation by esterases. Amiodarone has many side effects due to its very complex pharmacokinetic profile: extremely long elimination time and metabolite accumulation. Shorter-acting analogs provide for the control of pharmacokinetic properties and alleviate long-term toxicity.

Pro-Drugs¶

Prodrugs are inactive (or less active) drug analogs which are specifically metabolized to the pharmacologically active drug. The chemical change is usually designed to improve some deficient physicochemical property, such as membrane permeability or water solubility, or to overcome some other problems, such as overly rapid elimination or a formulation difficulty. Prodrugs can also be used to bring the drug to certain organs or cells in which the drug action is required. Examples of prodrugs are shown here.

articles

Metabolic Considerations in Prodrug Design Balant LP and Doelker E Burge's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery, Vol. 1 Wiley Wolff ME

Chemical Aspects of Selective Toxicity Albert A Nature 182 1958

Prodrug and Antedrug: Two Diametrical Approaches in Designing Safer Drugs Lee HJ, Cooperwood JS, You Z, and Ko DH Arch. Pharm. Res. 25 2002

Low Molecular Weight Prodrugs Stella VJ, Ed. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 19 1996

Design of a Novel Oral Fluoropyrimidine Carbamate, Capecitabine, which Generates 5-Fluorouracil Selectively in Tumours by Enzymes Concentrated in Human Liver and Cancer Tissue Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, Sawada N, Ishikawa T, Mori K, Shimma N, Umeda I, and Ishitsuka H Eur. J. Cancer 34 1998

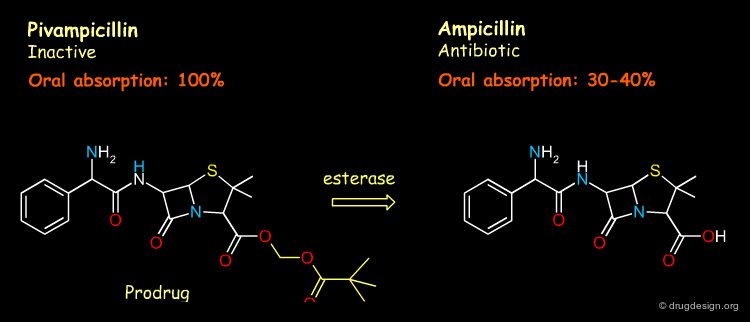

Oral Absorption¶

Increasing the lipophilicity of ampicillin is achieved by masking its acidic functional group which results in significantly better oral absorption.

Prolonged Activity¶

The Haloperidol prodrug is administered by the intramuscular route, in oil. Thus, the prodrug exhibits a sustained-release profile due to its high lipophilicity and subsequent slow release from injection site.

Improved Formulation¶

By producing a derivative with greatly depressed water solubility, the unpleasant taste of chloramphenicol is masked in oral dosage forms.

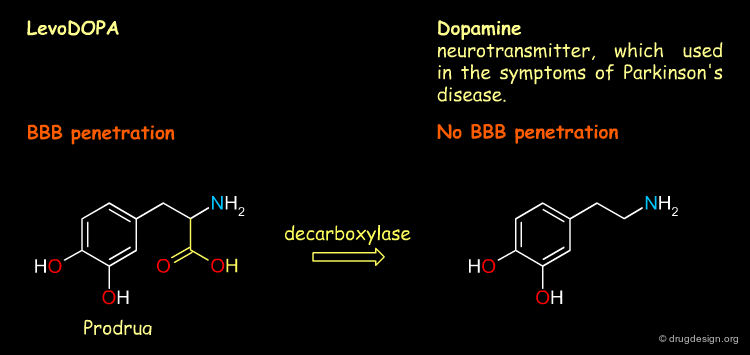

BBB Penetration¶

The prodrug levodopa can exploit the amino acid mediated transport systems for brain delivery and thus penetrates the BBB barrier easily.

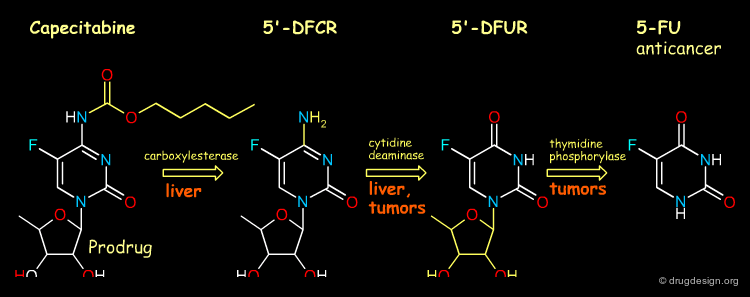

Tumor Targeting¶

Capecitabine was designed to generate 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) preferentially at tumor sites, and as a consequence to reduce its adverse effects. This tumor selectivity is achieved through exploitation of the significantly higher activity of thymidine phosphorylase in tumor tissue compared with healthy tissue.

Excretion¶

Excretion¶

Excretion is the irreversible process by which drugs and metabolites are removed from the body. The kidneys are the major organs of excretion. Other routes of excretion include the intestine, bile, saliva, sweat, breast milk and lungs; however these routes are relatively minor.

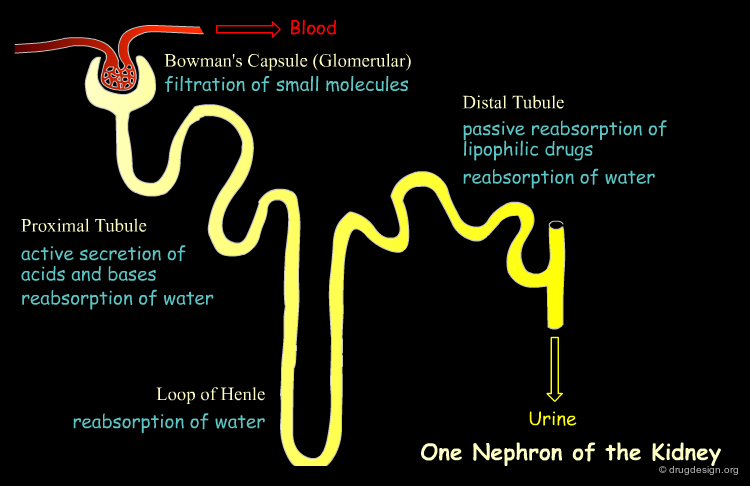

Renal Excretion¶

Excretion of substances by the kidneys into the urine is the primary route of drug excretion. The functional unit of the kidney is the nephron in which there are three major processes to consider: glomerular filtration, tubular secretion and tubular reabsorption.

Glomerular Filtration¶

Glomerular excretion takes place in the glomerulus (the very vascular beginning of the nephron). Small molecules (lipophilic or hydrophilic) including water, easily pass through the sieve-like glomerular endothelium (molecular weight cut-off 20,000 Da) into the nephron tubule, leaving behind blood proteins (including protein bound drugs) and blood cells. The rate of glomerular filtration varies from individual to individual and depends greatly on the blood pressure. In average healthy individuals, about 20% of the blood which enters the glomerular is filtered at a rate of 120 ml/min (190 lit/day). About 99% of the filtrate will be reabsorbed back into the blood in the subsequent stages.

articles

A More Accurate Method to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate from Serum Creatinine: a New Prediction Equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, and Roth D Ann. Intern. Med. 130 1999

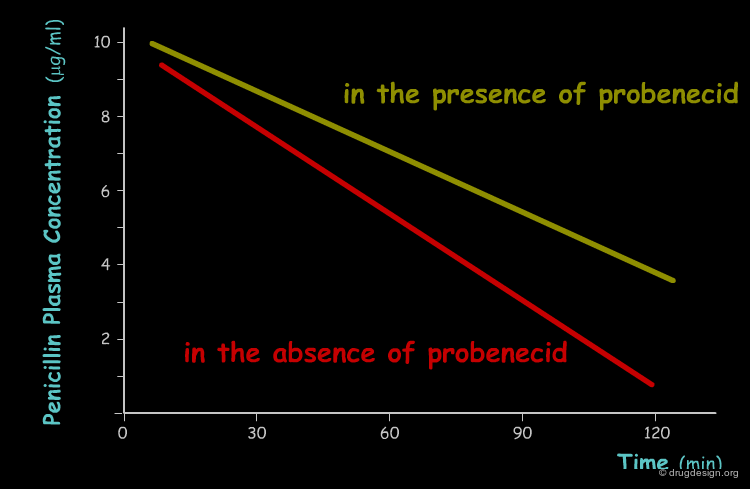

Tubular Secretion¶

Tubular secretion, which occurs in the proximal section of the nephron, is responsible for active transport of specific molecules out of the blood into the urine, including when most of the drug is bound to plasma proteins. Two separate systems exist, one that transports acids (e.g. penicillins, salicylic acid and many conjugated metabolites) and the other that transports basic substances (e.g. histamine, dopamine and choline). In each transport system, competition between different drugs can occur and lead to reduced excretion. For example probenecid is used to prolong the action of penicillins by inhibiting their excretion.

articles

Role of Transport Proteins in Drug Absorption, Distribution and Excretion Ayrton A and Morgan P Xenobiotica 31 2001

Benemid, p-(di-n-propylsulfamyl)-Benzoic Acid: Its renal Affinity and Elimination Beyer KH, Russo HF, Tillson EK, Miller AK, Verwey WF and Gass SR Am. J. Physiol. 166 1951

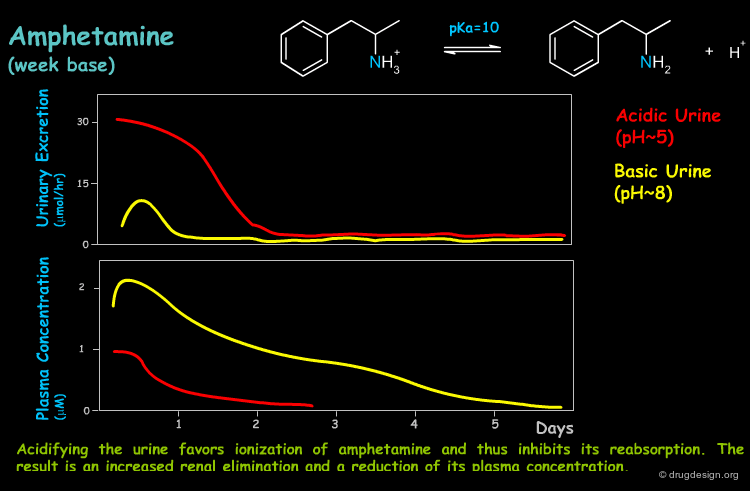

Tubular Reabsorption¶

All along the nephron tubule water molecules are reabsorbed, reducing the filtrate volume and thus increasing the solute concentration. As a result, and mainly towards the end of the nephron in the distal tubule, the concentration gradient is in the direction of reabsorption into the blood. In this case, lipophilic, non-ionized substances that can penetrate the tubule membrane are passively diffused and reabsorbed by the blood. Many drugs are weak acids or bases and therefore the pH of the filtrate (pH range from 4.5 to 8.0) can greatly influence their extent of tubular reabsorption, as can be seen in the example below.

articles

Amphetamine Metabolism in Amphetamine Psychosis Anggard E, Jonsson LE, Hogmark AL, and Gunne LM Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 14 1973

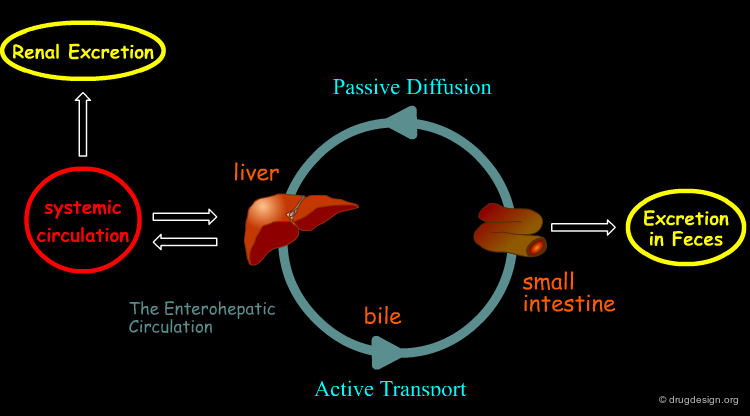

Biliary Excretion¶

Some drugs and their metabolites are excreted by the liver into the bile by means of active mediated transport. This includes drugs with a molecular weight > 300 gr/mol and with both polar and lipophilic groups, and this makes conjugated metabolites (mainly glucuronides). From the bile, the substance is excreted into the intestinal tract and there it can be eliminated from the body in the feces, or may be reabsorbed. The reabsorption occurs by passive diffusion and hence it is significant only for lipophilic non-ionized substances. However, enzymes in the intestinal flora are capable of hydrolyzing glucuronide and sulfate conjugates to release the (less polar) active drug that may be then reabsorbed. The result of this cycle is the creation of a drug reservoir which prolongs drug action.

Other Excretion Routes¶

Several more minor routes of excretion exist. These include exhaled air (pulmonary excretion) which is a major route for gaseous and volatile substances (e.g. gaseous anesthetics). Other routes such as saliva, sweat, and breast milk contribute only marginally to drug excretion. Note that excretion via breast milk may not be important to the mother, but it can be quite significant to the breast fed infant. Drug and drug metabolites are excreted into the milk by passive diffusion. Basic substances can be trapped in the milk since the milk is more acidic (pH ~6.5) than the blood plasma.

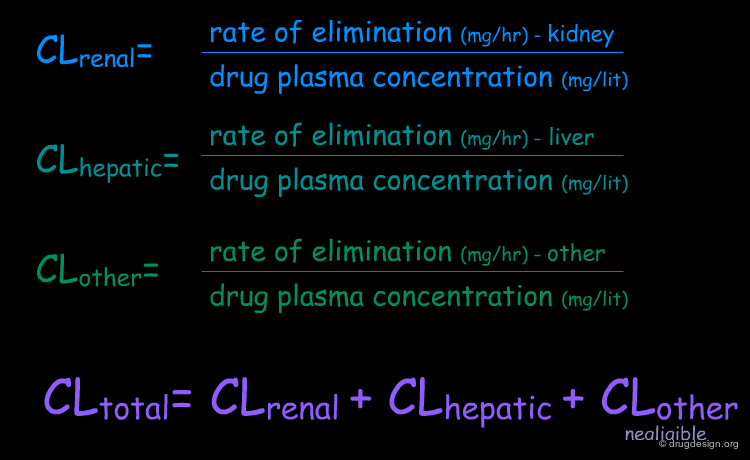

Clearance¶

Clearance (CL) is one of the most important parameters in pharmacokinetics. It is simply the rate of elimination of the drug relative to its plasma concentration, or in other words, the volume of plasma cleared of drug per unit time (e.g. ml/min). Clearance is an additive parameter; therefore the total elimination of a drug from the body is the sum of the clearance by all routes.

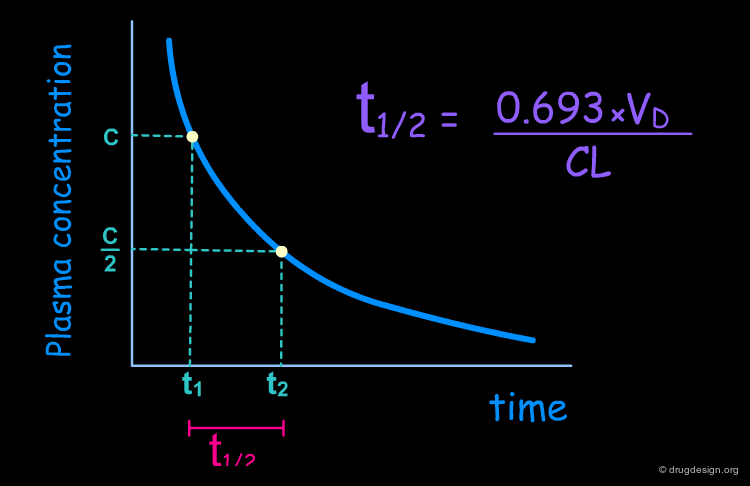

Half-life¶

Half-life (t1/2) is the most common measure of the duration of drug action. It is the time required for the concentration of the drug in the plasma to decrease by one-half (50%). Most drugs are eliminated according to first order kinetics, thus the amount of drug that is eliminated is directly proportional to the amount of drug that remains in the plasma. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the plasma is in equilibrium with only one compartment with a volume equal to the volume of distribution. In this simplified model the half-life can be derived from the independent parameters of clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (Vd), as indicated in the formula below.

ADME in Drug Design¶

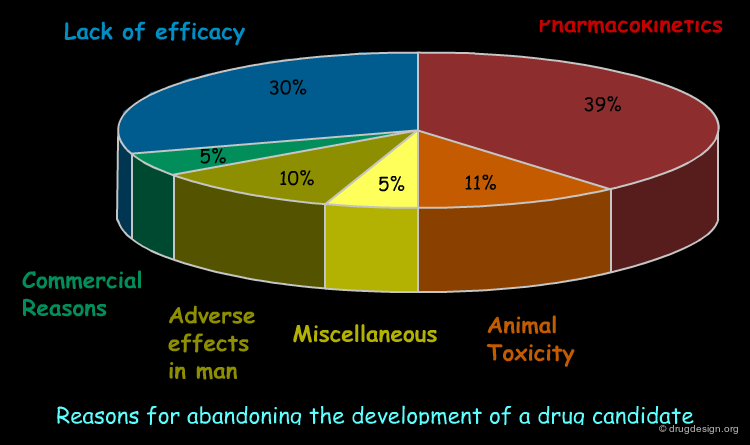

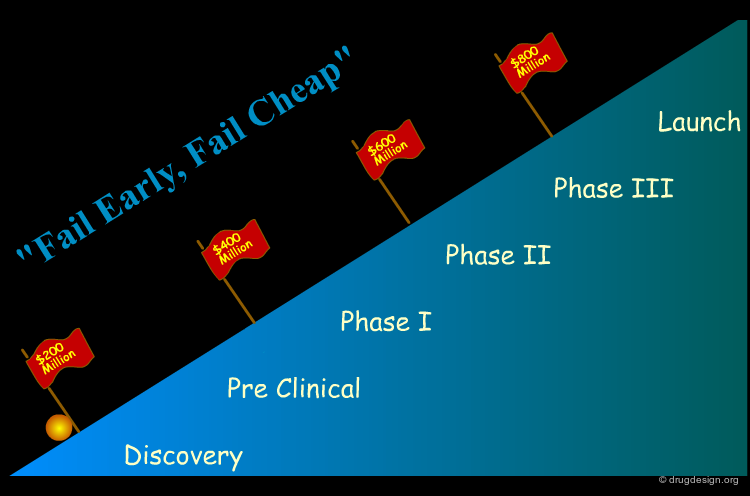

Failures in Drug Development¶

There are numerous examples in the pharmaceutical industry of initially very promising drug candidates that entered the development pipeline but that were abandoned after problems were encountered in later stages (e.g. insufficient pharmacokinetics). The diagram below presents a statistical analysis of the reasons why drug development is discontinued. Indeed, about 40% of drug candidates that enter clinical trials are finally discarded because of inadequate ADME-Tox properties.

articles

Managing the Drug Discovery/Development Interface Kennedy T Drug Discov. Today 2 1997

Risks in New Drug Development: Approval Success Rates for Investigational Drugs Dimasi JA Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 69 2001

Challenge of R&D Planning¶

A reliable filter for selecting good candidate drugs for development would result in enormous time and cost savings for R&D. Pharmaceutical companies try to move ADME evaluations into early discovery stages. Their approach is to develop more advanced experimental and in silico ADME models. Ideally, ADME evaluations should be conducted in parallel with activity and selectivity assays to enable all properties to be optimized simultaneously.

articles

The Price of Innovation: New Estimates of Drug Development Costs DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, and Grabowski HG J. Health. Econ. 22 2003

High-Throughput ADME Evaluations¶

In recent years the emergence of (ultra) high-throughput screening (HTS) and combinatorial chemistry has dramatically enhanced the capacity of biological screening and chemical synthesis. This situation has created an unprecedented demand for early information on the ADME properties of a large number of compounds. To meet this demand various high-throughput ADME screens have been developed. Moreover, computational predictive models of ADME properties have also been developed to further expand the ADME support of discovery.

In Silico Prediction of ADME Properties¶

Reliable in silico tools that predict specific ADME parameters from chemical structure alone would be extremely precious. They would be extremely useful for the design of new compounds or compound libraries, for filtering screening results, and for assessing the potential of early hits and leads. This would facilitate the selection of drug candidates and their successful development with superior ADME properties.

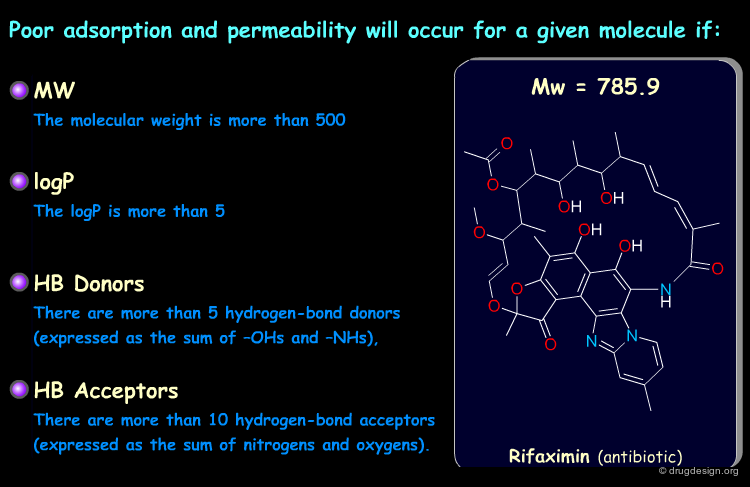

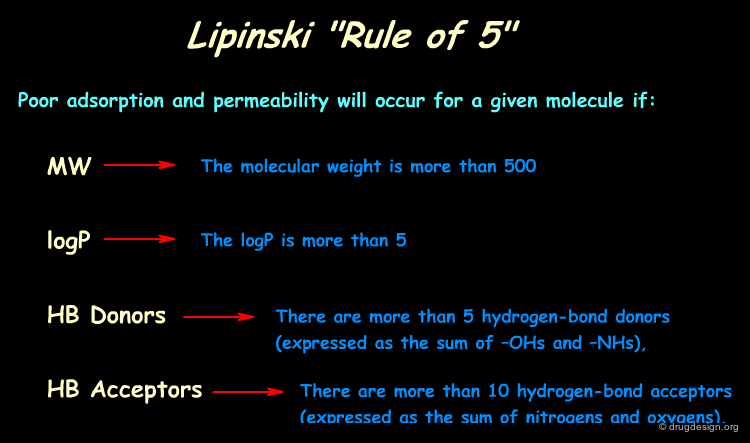

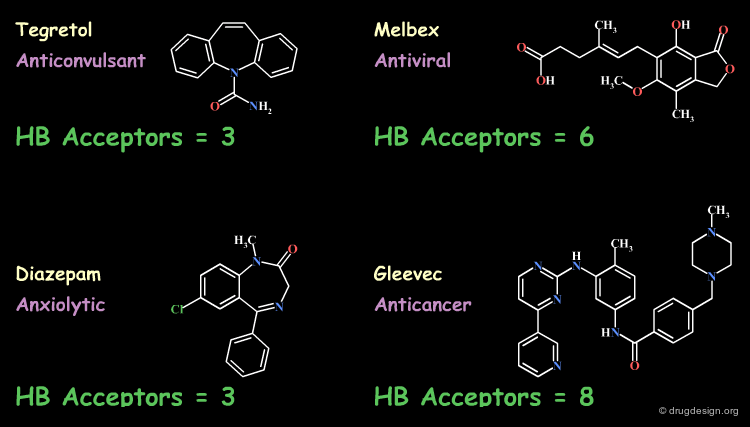

Lipinski Rules and Drug-Like Properties¶

In silico predictive ADME aims at assessing the "drug-likeness" of compounds from information derived from their chemical structure. Based on analyses of the World Drug Index (WDI) Lipinski developed the now popular "Lipinski's rule of five" (named because of its emphasis on the number 5 and multiples of 5) which predicts in a simple manner the drug-likeness of a molecule (see below, note that each item is clickable).

articles

Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Setting Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, and Feeney PJ Adv. Drug. Del. Revs. 23 1997

More Insights into ADME Predictions¶

How can the physicochemical properties of a drug be predicted? How can these properties be used in building a predictive ADME model? How is it possible to map out the potential interest of a new chemical structure solely from its molecular structure? All these questions will be addressed in the chapter on "ADME Predictions".

Copyright © 2024 drugdesign.org